Collapse and the Consensus Trance

The Stories That Blind Us to Reality

Editor’s note: This is the second essay in my collapse series. The first introduced a framework for understanding collapse; this one asks a harder question: why is collapse so difficult for most people to see, even when the evidence is everywhere?

Introduction: A World We Cannot See

Collapse surrounds us, yet most people cannot see it. We live through record-breaking heatwaves, vanishing ice, mass extinctions, and economic volatility, but these signals are routinely translated away - cast as anomalies, temporary setbacks, or even opportunities. Collapse is not hidden because the evidence is unclear; it is hidden because our culture is organised to prevent us from seeing it.

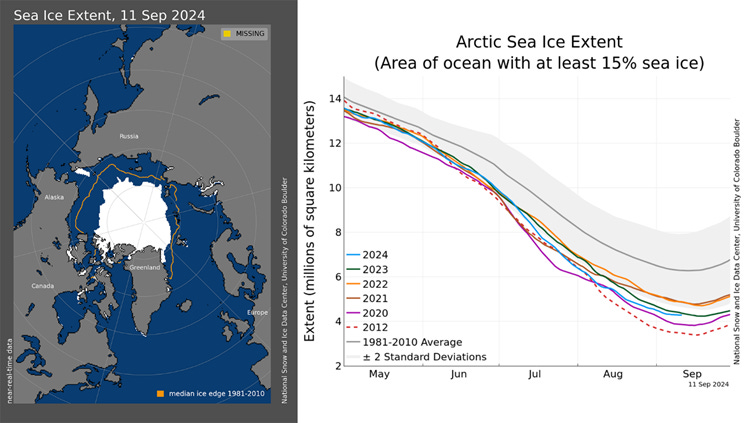

Consider the Arctic. In September 2024, the Arctic Sea ice minimum fell to just 4.28 million km² - the 7th lowest in the 46-year satellite record. The trend is unmistakable, and the consequences are profound: loss of albedo, destabilised weather systems, disrupted food chains, and rising seas. Yet instead of confronting what this means, public discourse reframes it: a temporary fluctuation, a call to innovate, or even an opportunity for new shipping routes. In this essay I argue that cultural filters are what make it invisible.

Fig 1: The map on the left shows Arctic Sea ice extent for September 11, 2024, at 4.28 million square kilometres (1.65 million square miles). The graph on the right shows Arctic Sea ice extent as of September 11, 2024. (Source: National Snow and Ice Data Centre, 2024)

In my Collapse Framework essay, I mapped six domains that show the structural forces driving decline. But understanding the pattern is only part of the challenge. The harder question is: why is collapse so difficult to perceive at all?

This essay explores that difficulty. Drawing on the anthropologist Charles Tart’s notion of the “consensus trance,” it examines how societies create shared illusions to maintain stability under the weight of truths too heavy to bear. At the core of this trance lies what can be called epistemic ambivalence; the capacity to know and not-know at the same time. We register collapse at one level, but continue to act as though it were distant or negotiable.

The journey begins with the trance itself, then traces the paradox of ambivalence, the cultural stories that sustain it, the misdirection of anger, the cracks that are beginning to show, and finally the fragile possibility of stepping outside it.

Chapter One: The Consensus Trance

A trance is not only an individual phenomenon. Entire civilisations can be held in collective hypnosis.

The anthropologist Charles Tart coined the phrase “consensus trance” to describe how societies condition individuals into shared ways of seeing and not-seeing. From birth, we are trained to inhabit it. We learn the categories, values, and priorities that sustain industrial culture: that human ingenuity can overcome natural limits, that economic growth equals progress, and that collapse happens only to other, “less advanced” societies.¹

This trance is not accidental, but maintained through institutions that reproduce its logic. Schools drill us into obedience to industrial rhythms - clocks, bells, productivity, competition. Media saturates us with images of breakthrough and imminent renewal, reinforcing the myth that technological progress is perpetual. As Chomsky and Herman observed in Manufacturing Consent, media systems do not merely reflect reality but actively shape it, policing the boundaries of what can be thought and spoken.² Politics offers the appearance of choice, but all mainstream parties converge on the same commitment to growth. Even science is often co-opted, securing funding through techno-solutionist promises or framing ecological crises as engineering puzzles rather than structural limits.³

The trance is also ritualised in daily life. Advertising, national holidays, even the architecture of cities encode the myth of progress. Collapse becomes not only unimaginable but impolite, taboo, even deviant. When ecological limits intrude - wildfire smoke choking a city, flooded homes on the evening news, empty supermarket shelves after a supply shock - they are reframed as anomalies, temporary setbacks to be corrected by innovation, markets, or political resolve.⁴

Like the air we breathe, the trance is invisible because it is total. Even when reality intrudes, we quickly translate it back into familiar terms. What remains most firmly unspoken is the implication of overshoot: contraction and die-off. William Catton warned that overshoot cannot resolve without a reduction in population, yet this reality is so intolerable that it is almost never acknowledged, even in ecological debate.⁵

Chapter Two: Epistemic Ambivalence

We know and not-know at once. Collapse is both visible and invisible, believed and disbelieved, acknowledged and avoided.

This ambivalence is a layered consciousness: to know collapse is real, yet to behave as though it is not. We scroll past footage of burning forests, register the gravity, and then book a holiday flight or check our pension fund as though the world were stable.⁶ The knowledge is there, but it is partitioned - allowed into awareness only briefly, before being folded back into routines that depend on ignoring it.

This ambivalence is not an individual failing - it is the natural outcome of being socialised into the consensus trance. To fully acknowledge collapse would risk alienation from community, despair, or paralysis. Therefore, we compartmentalise and maintain a surface adherence to the trance, while allowing collapse knowledge to remain in the margins of thought, accessed only in moments of crisis.

What is rarely recognised is that this ambivalence may itself be adaptive. From an evolutionary perspective, humans survived not by confronting every threatening reality at full scale, but by selectively attending to what could be acted upon. The ability to know and not-know simultaneously may have shielded communities from paralysis in the face of uncertainty or overwhelming risk.⁷

As Ernest Becker observed in The Denial of Death, human culture itself can be read as a defence against unbearable truths, a way of constructing shared meanings that protect us from paralysis in the face of mortality. Terror Management Theory extends this important insight, showing how people cling to cultural narratives when confronted with existential threat - an insight that resonates with how ambivalence functions in the consensus trance.⁸

But what was adaptive when threats were local and intermittent becomes disastrous when threats are global and systemic. Ambivalence, once a survival mechanism, now locks us into inertia. It enables us to acknowledge ecological breakdown at the level of rhetoric (net zero targets, green growth) while remaining embedded in the very behaviours and institutions that ensure overshoot and collapse.⁹

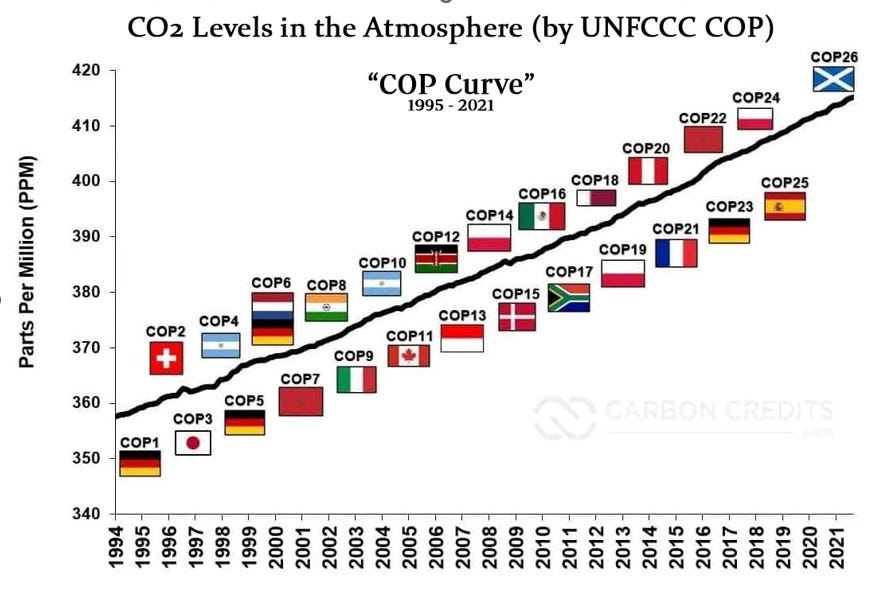

Figure 2 illustrates this paradox starkly: as climate summits multiplied, so have CO₂ emissions. Ritualised politics provides reassurance, while the underlying trajectory remains unchanged.

Fig 2: CO₂ Levels in the Atmosphere and COP Conferences 2023. Visualisation via CO₂ Earth (source: Global Carbon Project)

If you’ve ever felt torn between knowing collapse and still living within normal routines, this is not hypocrisy or weakness, but the cultural condition we all inhabit. When you begin to see through the trance, the loneliness that follows is not madness. It is simply the disorientation of noticing what others cannot.

Chapter Three: The Stories That Blind Us

The trance is held together by stories. They do not just entertain, they decide what is real.

The Story of Progress. History is cast as a linear ascent from ignorance to enlightenment, scarcity to abundance, and barbarism to civilisation. This blinds us to the fact that industrial growth was a one-time windfall built on fossil fuels and ecological liquidation.⁶ Collapse is cast not as part of history’s cycles but as unthinkable regression.

The Story of Human Exceptionalism. Humans are imagined as separate from, and superior to, the rest of life. We are made in God’s own image. This authorises exploitation, erases ecological dependency, and sanctifies growth as destiny.

The Story of Control. This is the conviction that science and technology can master complexity and risk. It fuels fantasies of geoengineering, space colonisation, and “decoupled growth.” Yet thermodynamics tells us that no complex system escapes energetic limits.¹⁰

These stories do not merely obscure, they also pacify. They provide reassurance whenever reality threatens to intrude. Progress promises that disruptions are only temporary, and exceptionalism promises that collapse is for others, not us. Control promises that ingenuity will restore order.

Together, these narratives not only blind us to ecological reality but reinforce epistemic ambivalence. They give us something to fall back on when awareness of collapse begins to surface. This is why even when the stories crack, they rarely break. They are not just myths, but a kind of civil religion - sacralised, defended, and enforced through cultural taboo. To question them is to risk heresy.

Chapter Four: Anger and the Illusion of Villains

For many, the first crack in the trance is anger.

The first impulse of collapse-awareness is often rage: at Trump, at Musk, at Exxon, at Google. Civilisation seems to be unravelling, and it is easy to pin the blame on elites who profit from destruction, or corporations that accelerate extraction.

This anger is not meaningless, because it shows moral concern. It shows care for the living world, and for each other. Grief often passes through anger on its way to clarity. But if we stop at anger, we risk mistaking symptoms for causes.

Our elites, past and present, are not the root of collapse but expressions of civilisation in overshoot. They embody the defects of civilisation’s qualities: agriculture that erodes soil, industry that pollutes, growth that depletes, and complexity that creates fragility. They are tools for channelling energy and resources into continued expansion. Not aberrations, but the predictable products of a dissipative structure forced beyond limits.

These figures are best understood as ‘Dissipation Nodes’: structural conduits in the system that channel and amplify the flow of energy and resources. The role of a dissipation node is to accelerate throughput, whether in the form of Amazon’s supply chains, Musk’s techno-utopian ventures, or Exxon’s extraction.

Focusing anger on villains can feel righteous, but it keeps us tethered to the illusion that collapse is a matter of bad actors. The consensus trance thrives on this story, because it reassures us that if only different people were in charge, the trajectory could change. But the flaw is not in the individuals. It is in the structure of civilisation itself.

Anger has its place, but the deeper clarity is this: collapse is not a morality play. It is structural, not personal. This does not mean anger is illegitimate. For those who bear the brunt of oppression, anger at leaders and systems can be an essential act of survival. My point is that anger alone cannot explain or resolve collapse, which runs deeper than any individual figure.

Of course, I write this from the position of the global North, where collapse is often mediated through elites, institutions, and media. Elsewhere, collapse is not refracted through villains but lived directly; in drought, displacement, or hunger. Recognising this is important.

Chapter Five: Cracks in the Trance

Reality is breaking through. Our stories no longer match lived experience.

Climate disasters intensify faster than predicted, and economic volatility exposes fragility. Biodiversity loss accelerates beyond our capacity to catalogue it. Younger generations, disillusioned by promises of stability, are questioning the inherited narratives of progress and control.⁶

These cracks create dissonance. The stories no longer fit. Yet rather than shattering the trance, dissonance often deepens ambivalence. Psychologists describe this as normalcy bias: the tendency to interpret even extreme shocks as temporary deviations.¹¹ System justification theory goes further, showing how people defend existing arrangements precisely because they are failing, finding comfort in the familiar even when it harms them.¹²

Figure 3 shows that while majorities report being ‘very concerned’ about climate change, far fewer alter travel, diet, or energy use. This is collapse awareness retreating into ambivalence - concern without transformation, and acknowledgement without change.

Fig 3: Global Warming - Concern vs Action (U.S. data) (source: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication)

This dynamic reveals the resilience of consensus trance. It adapts to evidence by absorbing it into its narratives. Extreme weather is presented as proof of the need for more innovation. Economic crises justify further financialisation. Social unrest is framed as a governance issue, not a systemic limit.

The cracks are therefore ambiguous. They expose fragility but also reveal the strength of our commitment to the trance. They offer opportunities for awareness, but awareness without new narratives or actions almost always retreats back into ambivalence.

Chapter Six: Beyond the Consensus Trance

To step outside the trance is not to escape it, but to inhabit collapse differently.

The first step is accepting limits. Collapse is not a deviation from modernity but its predictable outcome. Overshoot, energy imbalance, and biodiversity loss cannot be solved by the same logics that created them. Joseph Tainter reminds us collapse is simplification, not failure.¹⁰ William Catton shows overshoot is not a policy error but an ecological process.⁵

Importantly, collapse is not a singular event but a drawn-out process: a long descent of simplification, contraction, and dislocation. Overshoot unwinds over decades, not days, which is why collapse-awareness must grapple with endurance as much as endings.¹³ This recognition is not widely present in collapse discourse. Many accounts stop at ecological limits or economic contraction. What is added here is the insistence that to see collapse clearly, we must also change how we see and how we live within it.

The second step is seeing. Collapse spans physics, ecology, politics, psychology, and meaning all at once. No single discipline or story is enough. Awareness requires us to weave together different ways of knowing until the picture sharpens. However awkwardly, we have to become multidisciplinary beings, because collapse itself is multidisciplinary.

For those who have already begun to see beyond the trance, this framing explains the loneliness: you are not maladjusted; you are simply perceiving what others cannot. For those only beginning to sense collapse at the edges, recognising ambivalence as a cultural pattern can ease self-blame - the difficulty isn’t personal weakness but a collective condition.

The third step is narrative. If the consensus trance is held together by stories, then alternative stories can open cracks of another kind: not dissonance but possibility. Stories grounded in ecology, reciprocity, and continuity. Stories where human fate is not separate from the Earth but entwined with it. This is the counter to the trance stories; of progress without limits, of salvation through technology, of mastery over Earth. Where those stories numb, these ones disclose.

Thinkers such as Vanessa Andreotti describe this work as “hospicing modernity” - accompanying the decline of a civilisation with honesty and care, without illusions of rescue.¹⁴

Breaking ambivalence does not mean dwelling in despair. It means remembering that collapse is not only destruction but disclosure. It exposes the failure of the stories we inherited and creates the conditions for renewal: regenerating soils, restoring ecosystems, reweaving human–Earth relationships.

The fourth step is praxis. Collapse is not only intellectual but embodied. It arrives in grief, stress, numbness, and the small rituals that carry us through; feeding the robins, creating habitat for dormice, growing and sharing food. These are not marginal or frivolous. They are ways of inhabiting collapse differently, of stitching fidelity and solidarity into a fraying world.

To step beyond the consensus trance is not to leave collapse behind but to live inside it with greater clarity. Limits acknowledged, perception widened, stories reimagined, and praxis embodied; these are the bearings that allow us to inhabit collapse differently. They also open onto the deeper work of remembering what it means to belong within the web of life once more.

Conclusion: Seeing Through the Stories

Collapse is not hidden because the evidence is weak. It is hidden because we live inside a consensus trance: a socially shared hypnosis sustained by ambivalence and cultural stories.

This essay has traced how that trance blinds us, how ambivalence allows us to know and not-know at once, how anger misdirects us, and how cracks appear without breaking the spell. Seeing these patterns does not dissolve them, but it gives language to the bewilderment many collapse-aware people feel - the loneliness of noticing what others cannot.

To see collapse clearly is to recognise not only destruction, but disclosure - the unveiling of stories that no longer serve. In that disclosure lies the necessity of remembering ourselves differently; as ecological beings once more.

This is the second essay in an ongoing series. The next will explore what it would mean for humans to live once again as ecological beings. Subscribe below if you’d like it delivered directly, and please do share reflections or questions in the comments - they help shape where this series goes next.

References

Tart, C. (1986). Waking Up: Overcoming the Obstacles to Human Potential. Boston: Shambhala.

Herman, E., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon.

Bury, J. (1920). The Idea of Progress: An Inquiry into its Origin and Growth. London: Macmillan.

Ehrenreich, B. (2009). Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking Is Undermining America. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Catton, W. (1980). Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens, W. (1972). The Limits to Growth. New York: Universe Books.

Becker, E. (1973). The Denial of Death. New York: Free Press.

Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & Greenberg, J. (2015). The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life. New York: Random House.

IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge University Press.

Tainter, J. (1988). The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Jost, J., Banaji, M., & Nosek, B. (2004). “A Decade of System Justification Theory.” Political Psychology, 25(6), 881–919.

Greer, J. M. (2008). The Long Descent: A User’s Guide to the End of the Industrial Age. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers.

Andreotti, V. (2021). Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). (2024). Arctic sea ice likely reached its annual minimum extent on September 11, 2024. NSIDC.

Global Carbon Project. (2023). Global Carbon Budget 2023. Earth System Science Data, 15, 2295–2362. Visualisation via CO₂.Earth.

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Rosenthal, S., Kotcher, J., & Bergquist, P. (2021). Climate Change in the American Mind: December 2020. Yale University and George Mason University. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

Thanks for the kind words 🙏 Yeah, it's heavy but it's still better to know 💚

I was fascinated by the notion of “hospicing modernity “. It made me wonder if there’s a role for “collapse doulas” who like death doulas could help shepherd us to the other side of ecological death with sanity and grace?

It’s interesting to compare the denial of individual death with our denial of civilizational collapse. I also like framing both as simplify, simplify as Thoreau observed…