Collapse: Living Without the Future We Were Promised

What happens when the future stops organising behaviour

Editor’s note: My earlier essay, Collapse: A Framework sets out the structural dynamics of ecological overshoot and collapse.

This essay is personal. It draws on ecological economics, collapse studies, behavioural science, and my own professional experience in public systems. The claim is simple: when reality asserts itself and options disappear, human cognition and ethics reorganise accordingly.

If you recognise parts of yourself here, that is not coincidence.

Chapter 1: The ground we stand on

Decline becomes visible when the future stops behaving as promised. The reason lies in the physical conditions that made those promises possible.

Modern civilisation rests on a physical substrate rarely acknowledged in everyday life. Energy, materials, and ecological stability set the limits within which human futures unfold.

Industrial society emerged from a one-off energy windfall. Fossil fuels supplied concentrated, portable energy at unprecedented scale, enabling expansion through accelerated drawdown of the natural world.

Everything else followed.

The Limits to Growth model demonstrated that exponential energy and material throughput in a finite system produce ecological overshoot and subsequent decline regardless of political or economic ideology (Meadows et al., 1972).¹

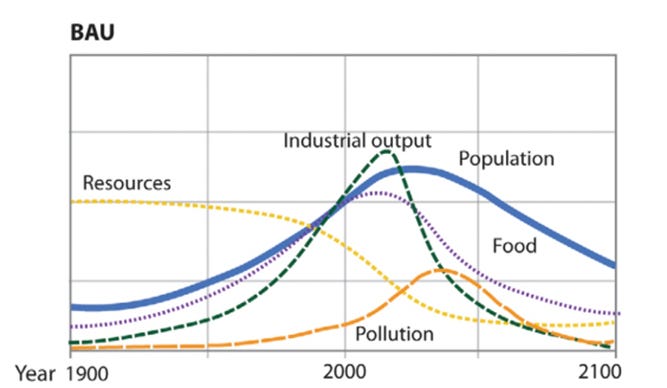

When Graham Turner compared forty years of historical data against the Limits to Growth model’s business-as-usual scenario, he found reality tracking the projections with remarkable precision. Population growth, industrial output, food production, and pollution all followed the standard run trajectory.²

Fig 1: Adapted from Limits to Growth 30-year update. Source: Resilience.org (2021)³ Copyright: Meadows et al. (2004)⁴

The model indicated collapse beginning around 2015, defined as the point where per capita industrial output begins sustained contraction (Turner, 2014).² The Club of Rome’s 2022 update confirms we are still broadly in line with the standard run’s trajectory.⁵

William Catton framed industrial civilisation as a drawdown economy, temporarily exceeding carrying capacity by consuming natural capital as if it were income (Catton, 1980; Rees, 2023).⁶⁷

Seventy-five billion tonnes of fertile topsoil are removed by erosion each year. Soil forms at rates under 0.2mm per year, and industrial agriculture strips it at rates exceeding 1mm per year. The arithmetic is unforgiving. Agricultural land in the United States loses soil ten times faster than it regenerates; in China and India, the rate is thirty to forty times faster.⁸

In human terms, the ecological crisis is ultimately a food crisis. Soil loss, aquifer depletion, fertiliser dependency, and climate instability converge on agricultural systems designed for abundance. The mathematics of feeding 8.2 billion people relies on conditions already eroding.⁸

Joseph Tainter showed that societies solve problems by adding complexity; administrative layers, technologies, and institutions, until the marginal returns on complexity turn negative (Tainter, 1988).⁹

When the NHS was established in the UK, relatively simple institutional arrangements produced extraordinary returns: basic access to doctors, nurses, sanitation, and antibiotics dramatically improved population health. Over time, the system accumulated layers of coordination, oversight, and response functions to manage rising demand, political scrutiny, and institutional risk.

Some NHS teams and organisations now exist primarily to manage the consequences of systemic strain; complaints, MP queries, litigation, and individual funding requests, rather than to deliver new health improvements. This exemplifies diminishing returns on complexity.⁹

Decline operates as the normal behaviour of overshot systems returning toward constraint.

The academic literature has long examined collapse as a systemic outcome of overshoot. For humans who accept this trajectory, the question has become how we live once the predictive stories that sustained modern life no longer hold meaning.

Chapter 2: The moment prediction fails

Industrial societies are organised around prediction.

Education assumes hard work now produces security later. Career ladders assume advancement. Pension systems assume institutional continuity decades ahead. Governments coordinate around ten-year targets. Financial markets price assets on projected growth.

These structures depend on expanding material throughput. Tim Jackson shows that liberal democracies stabilised themselves politically by distributing the gains of growth across successive decades (Jackson, 2009).¹⁰ Societies held because each cycle delivered more surplus than the last.

Joseph Tainter’s analysis of complexity clarifies the structural basis. Societies solve problems by adding administrative layers, technologies, and coordination mechanisms. Each layer carries an energy cost. When surplus expands, returns justify the added complexity. When surplus contracts, maintenance absorbs a growing share of available energy (Tainter, 1988).⁹

Culture performs a parallel function. Ernest Becker argued that shared narratives buffer existential anxiety by embedding individual lives within meaningful futures (Becker, 1973).¹¹ Terror Management Theory demonstrates that when systemic threat becomes salient, people defend those worldviews more strongly (Greenberg et al., 1986).¹²

Modern institutions and identities therefore rest on two linked conditions: material expansion and a future that can be used to organise behaviour. When expansion falters, predictive systems strain and the future becomes more uncertain.

Plans continue and targets remain. Institutional language persists, yet outcomes diverge from projection. Effort produces diminishing returns and responses arrive late. They address the world as it was, not as it is.

Normalcy bias explains part of the persistence. People interpret disruption as temporary deviation rather than structural change (Ripley, 2008).¹³ System justification theory shows that attachment to existing arrangements intensifies under threat (Jost & Banaji, 1994).¹⁴

Belief gradually erodes. Under sustained constraint, human cognitive systems recalibrate.

Research on scarcity shows that constrained environments narrow attention toward immediate demands (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013).¹⁵ Cognitive bandwidth concentrates on pressing limits and problems rather than distant abstraction. The effect follows from conditions, not beliefs.

Organisational psychology documents the threat-rigidity effect: under pressure, behavioural variance declines, decision pathways narrow, and experimentation reduces (Staw et al., 1981).¹⁶

Life history theory demonstrates that in unstable environments, organisms adopt shorter time horizons and prioritise immediate payoffs (Ellis et al., 2009).¹⁷ When future conditions cannot be relied upon, long deferral loses strategic value.

Behavioural ecology supports the same pattern. Under uncertainty, organisms weight information that guides direct action more heavily than information that doesn’t. Adaptive behaviour depends on how well an organism reads its environment. The more accurately it detects relevant constraints and opportunities, the more effectively it can adjust its actions to match changing conditions (Dall et al., 2005).¹⁸

Across these literatures, a consistent finding emerges: Persistent constraint reorganises cognition. Attention concentrates. Time horizons rescale. Behaviour aligns with feedback rather than projection.

These shifts arise from altered conditions.

Variation appears in how quickly this recalibration occurs. Pellicano and Burr propose that autistic perception relies less heavily on socially reinforced priors and more on immediate input (Pellicano & Burr, 2012).¹⁹ Reduced weighting of prior expectation increases sensitivity to predictive mismatch.

Environmental instability produces comparable effects in neurotypical populations. Exposure to unreliable futures, violence, or chronic precarity lowers dependence on deferred reward and increases present orientation (Nettle, 2010; Bulley & Pepper, 2017).²⁰²¹

Sensitivity differs, but the mechanism does not. When surplus narrows and prediction weakens, cognition reorganises accordingly.

Perception tracks feedback. Ethical judgement aligns with consequence. Time horizons adjust to what can be followed. Attention moves toward maintaining function.

These are adaptive responses to constraint.

The next chapter examines this contraction through the lens of degrees of freedom.

Chapter 3: Degrees of freedom shrink

In physics, degrees of freedom describe how many independent variables a system can change within its constraints.

As constraints tighten, the range of possible behaviour narrows and actions become channelled. Outcomes become more predictable because fewer states remain accessible.

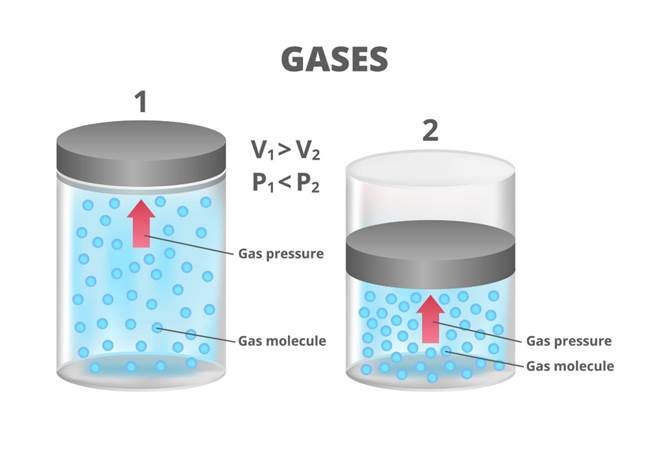

For example, a gas in a container illustrates degrees of freedom. When the container is large, molecules can move in many directions and explore many possible states. As the container shrinks, movement becomes more restricted, collisions increase, and the range of possible behaviours narrows.

The gas does not choose a new strategy or optimise its behaviour; it reorganises automatically in response to constraint. Behaviour changes because degrees of freedom shrink, not because intention changes.

Fig 2: Degrees of Freedom: Gas in a container at decreasing volume (V) with increasing pressure (P). Source: Wikimedia Commons. (2025)²²

Human systems follow the same pattern.

Industrial civilisation developed within a period of exceptional surplus. Abundant energy, ecological margins, and institutional continuity created a wide field of possible futures.

Multiple paths could be explored, revised, or abandoned. Prediction functioned because the future reliably contained more options than the present.

Under decline, that condition reverses and material limits assert themselves. Surplus contracts, and degrees of freedom collapse.

The future contains fewer viable states than the present. Our behaviour reorganises in response.

Systems optimised for expansion do not contract symmetrically; they destabilise before they resize. Institutions built on growth continue to promise restoration even as the conditions that supported it narrow.

When decline is accepted as a condition rather than a threat, four domains reorganise together.

1. Perception reorganises around feedback. Attention turns toward signals that still return consequence and away from abstractions that no longer resolve.

2. Ethics come into focus. Moral judgment aligns with consequences rather than distant ideals. What matters is reducing harm, preserving function, and maintaining dignity where effects are actually felt.

3. Time horizons contract to the span over which conditions make sense. Planning aligns with what can be reasonably anticipated rather than abstract futures.

4. Attention and effort reallocate toward activities that still make sense. Cognitive and emotional energy concentrates on practices that function under constraint.

These reorganisations are adaptive. They arise from constraint rather than intention. As degrees of freedom collapse, behaviour follows the remaining channels available to the system.

Humans are the only species able to recognise overshoot and track its patterns across civilisational histories. That capacity for recognition does not increase degrees of freedom once limits are reached. Understanding constraint does not recreate options that were only possible under surplus. Delayed feedback limits our ability to respond before constraints assert themselves.

Awareness existed in every overshooting society, but it coexisted with rising structural commitments, because growth widened choices temporarily while contraction narrowed them systemically.

As limits assert themselves, the range of viable actions shrinks regardless of recognition. Behaviour becomes shaped by what functions under constraint, not by what we understand or believe. Under contraction, this pattern is expected.

In this context, awareness helps identify remaining paths rather than reopen those that have already closed.

Chapter 4: Perception: from abstraction to immediacy

As predictive horizons shorten, perception changes. Attention moves away from abstract futures and toward conditions that generate immediate feedback. This pattern is well documented across behavioural ecology and psychology.

Under sustained uncertainty, people focus on what they can influence directly. Long causal chains lose relevance when they stop guiding action. Immediate consequences come to dominate perception.¹⁸

In industrial societies, perception is trained toward abstraction. Futures are rendered legible through models, projections, and narratives that promise continuity; pensions, promotions, climate targets, growth forecasts, and performance metrics all displace risk into models and timelines rather than immediate experience.

Under decline, this orientation no longer tracks reality. The future ceases to act as a stable reference point and promises become detached from outcomes. Indicators that once carried authority (targets, strategies, forecasts) stop translating into lived experience.

Perception alters accordingly, and attention turns to that which still produces results. Fragility, delay, inefficiency, and breakdown take priority. Systems are no longer evaluated by stated purpose, but by how they behave under pressure.

This materially impacted my own work life. Markers of prestige and advancement that once held meaning lost their ability to stabilise anything that mattered. Titles, visibility, and institutional standing stopped correlating with coherent leadership.

My perception narrowed toward material conditions.

Staff wellbeing became a primary signal of institutional health. Organisational weak points drew attention because they predicted failure. Focus in these areas produced results in a world where abstraction increasingly did not.

Outside of work, permaculture attracted my attention for the same reason. It operates as a life-positive design framework explicitly oriented toward constraint and energy descent.

It trains perception toward flows, limits, feedback loops, and persistence under pressure. Yield is judged by whether something works where it is, not by how much it could produce in theory. Optimisation gives way to designs that tolerate failure and persist. Attention is drawn toward what responds to care, not toward what looks good in a quarterly report.²³

Once perception settles on feedback and limits, abstraction stops carrying the same weight. Actions are judged by whether they hold up. What matters is what endures under pressure.

Chapter 5: Ethics: from abstract justice to situated care

Ethical reasoning reorganises alongside perception.

High-energy societies support abstract moral systems. Surplus allows ethical frameworks to operate at scale, detached from immediate consequence. Justice is formulated as principle. Responsibility is spread thin, and harm is felt later - or to someone else, somewhere else.

As resources tighten, ethical judgement moves closer to home. What matters is how decisions affect the people and living systems within reach. Care, reciprocity, and accountability consolidate within bounded communities and institutions. Ethical weight concentrates where consequence is felt.

This is what ethics look like when surplus disappears. As systems strain, harm becomes immediately visible. Decisions register through what they do to people you know, not by whether they look right on paper. Ethical judgement reorganises around preserving function, reducing damage, and maintaining dignity under constraint.

In public systems, decisions are often constrained before they reach you. The choice is between staying close enough to reduce the damage or stepping back and leaving it to land without you.

I have chosen, at times, to stay close to decisions I disagreed with, because stepping away would not have prevented them; it would only have removed the possibility of mitigating their effects on staff or the citizens we serve.

This is ethical exposure. Under constraint, leadership often consists of absorbing moral discomfort so that others do not carry it alone.

In my professional life, this reorganisation expressed itself as a movement away from transformation narratives and toward staff protection, organisational resilience, community buffering, and institutional honesty. Under constraint, problems ceased to present as solvable.

Ethical action focused on harm reduction, resilience, and continuity within limits.

The language of improvement remained, but its organising power weakened. Operating this way is uncomfortable, but it keeps consequences closer to those who bear them.

Many of the people I work with retain no language for decline. They continue to speak in terms of recovery, growth, and transformation. Behaviour communicates something else. Burnout rises and retention destabilises, and communities fray under cumulative pressure.

Ethical action under these conditions operates through helping people remain intact while systems strain. Integrity becomes practical rather than aspirational.

Ethics narrow, then stabilise.

Within institutions, meaning persists at this level, even as larger aims lose coherence.

Chapter 6: Time horizons: from legacy to continuity

Time is one of the first abstractions destabilised by decline.

Industrial societies organise life around extended time horizons. Education, career progression, home ownership, pension systems, and institutional planning all assume a future that remains sufficiently stable for deferred reward to make sense. Individuals are trained to tolerate present discomfort in exchange for future security.

Jam tomorrow.

Institutions coordinate across decades on the assumption that conditions will broadly persist and improve. Governments commit to targets a decade in the future. This temporal structure depends on expanding throughput and reliable continuity. When energy and material constraints assert themselves, the future stops functioning as a dependable reference point.

Plans remain technically possible, but they stop matching what actually happens. Strategies continue even after the conditions they relied on have changed, and promises are made without a workable route to delivery.

This manifests as temporal incoherence. We lose confidence in retirement projections, and career trajectories become more uncertain. Institutional strategies expire before implementation, making way for the next planning round.

As ecological economist Tim Jackson has shown, prosperity narratives rely on deferred reward made possible by expanding throughput. When throughput contracts, deferral loses its organising role. Planning contracts to the span over which reality can still be followed.¹⁰

In my own life, this reorganisation expressed itself as a move from legacy thinking to continuity thinking. Focus on long-term outcomes stopped making sense. My attention moved toward whether an action stabilised conditions now and avoided compounding harm.

Planning remained, but it shortened to the span over which reality could be tracked. Commitments were made only where the terrain was still legible. Long-range ambition lost its pull, and day-to-day coherence mattered more.

Essay writing emerged from the same altered relationship with time. Others performed this work for me when I became collapse aware. Their writing held when institutional narratives dissolved, and I write to pay that forward.

In industrial societies, meaning is carried forward by institutions, plans, and shared futures. When those mechanisms weaken, meaning has to be maintained rather than assumed. Writing performs that work. It records what still holds meaning, preserves distinctions that would otherwise blur, and preserves continuity when long futures can no longer be assumed.

Writing becomes the work of keeping meaning intact when the future can no longer do it for us. It allows understanding to persist as institutional memory degrades and predictive narratives lose authority. When the future stops organising behaviour, continuity depends on what we choose to keep.

Time horizons did not collapse. They rescaled.

Chapter 7: Attention: energy follows constraint

Attention tracks energy.

When resources are plentiful, it disperses towards status, abstraction, and distant futures. Under constraint, it concentrates where return still registers; maintenance, repair, and care. Beliefs can be stated and values declared, but attention goes where conditions allow.

My attention redistributed gradually. Work calibrated towards sufficiency rather than advancement. Energy moved to activities that returned coherence. Ecological systems drew sustained attention because they persist under constraint. Writing absorbed attention because it stabilised understanding when external narratives failed.

None of this was planned. It followed from constraint.

What falls away are ambitions that depend on conditions no longer holding; what remains are obligations that can still be met.

Scale and visibility stopped mattering. Being seen as senior, influential, or strategically central stopped feeling worth the cost. I began paying closer attention to whether staff were coping, where friction was accumulating, which small changes actually reduced strain.

Outside work, attention settled on unglamorous things: soil structure, compost quality, biodiversity, and whether systems returned something usable for the energy put into them. Signals. They showed what strengthened with care and what degraded without it.

This reorganisation gets misread as disengagement. Reduced participation in future-oriented and performative projects looks like withdrawal. The difference shows in what continues. Withdrawal sheds responsibility. Adaptation doesn’t.

Attention remains directed towards maintenance, care, and work that still returns real effects. People adapting show up differently: fewer promises, shorter commitments, more emphasis on what can be sustained.

What disappears is speculative labour organised around outcomes that lack supporting conditions. The misreading happens when engagement is measured by ambition rather than sustained effort.

Chapter 8: Living without the future we were promised

The hardest part of accepting decline is losing the future that organised our lives.

Industrial societies trained people to orient towards promised outcomes: stability, progress, security, improvement. Education, work, savings, and status, all derived meaning from futures assumed to be reachable. When those futures dissolve, the loss registers as grief.

A transformation achieved, celebrated, and quietly reversed when the resources required to sustain it were withdrawn. The service shuttered, the team dispersed, and the old pressures returned. Entropy in institutional form.

Attention, ethics, and time horizons were calibrated toward futures that no longer hold. The future once justified deferral and sacrifice. When that justification weakens, only the sacrifice remains.

When the future stops organising behaviour, what remains is what still works.

From the outside this looks like retreat. From the inside it is adjustment to the terms at hand. The horizon shortens. Promises contract. Attention settles on what responds.

It shows up in shorter commitments, in the care taken with words, in the refusal to promise what cannot be delivered. It shows up in the decision to steady an institution rather than transform it, to protect a person rather than advance a plan.

There is no spectacle in this. No rhetoric of breakthrough or rescue. There is work that continues and work that falls away. Meaning resides in what is kept intact.

This is how people live when expansion is no longer the condition of life.

Chapter 9: Conclusion: adaptation, not ideology

Once decline is accepted, human perception, ethics, time horizons, and attention reorganise simultaneously. These responses are structural adaptations to shrinking degrees of freedom, not ideological choices.

The central failure of late industrial civilisation is not decline itself. It is the continued instruction to organise our lives around futures that are no longer possible. People are trained to plan, strive, and defer inside a temporal architecture that has already collapsed. The resulting distress comes from structural mismatch.

Living inside decline requires abandoning narratives that no longer align with reality. It requires acting without the promise of progress as justification. What matters now are coherence, reducing harm, and continuity under constraint. These are addressed locally. They do not resolve at scale.

For those who find themselves already reorganising along these lines, this essay offers confirmation. It is not an instruction manual. The changes described here are not chosen; they emerge.

For some readers, this will make sense of what they are already noticing. For others, it functions as a map of territory that may become legible later, under pressure. The examples here are mine, but the pattern is structural. Your reorganisation will look different and arise from your own constraints.

I work inside institutions I no longer assume will endure. That doesn’t absolve me of responsibility. When bureaucracies enter their late stage, energy is spent maintaining narrative coherence while structural cohesion weakens.

Entropy is not an event but a condition. In that context, the work is to support people, make trade-offs explicit, and reduce avoidable harm. The work is justified by what it prevents, not by how it ends.

To live inside decline is to stay engaged without pretending. It means letting go of actions that promise futures that can no longer be delivered, and supporting forms of life that still fit the world as it is. Meaning is found through care offered within limits.

This is what adaptation looks like when the future stops organising behaviour.

My writing will always remain free to access. If it resonated with you, please consider liking and sharing - that’s how this work travels. You’re very welcome to subscribe if you want to follow where these ideas go next.

References

1. Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens, W. W. (1972). The Limits to Growth. Universe Books.

2. Turner, G. M. (2014). Is Global Collapse Imminent? An Updated Comparison of The Limits to Growth with Historical Data. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute (MSSI) Research Paper No. 4.

3. Resilience.org. (2021). “Limits to Growth” chart / post referencing the 30-year update (online).

4. Meadows, D. H., Randers, J., & Meadows, D. L. (2004). Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. Chelsea Green Publishing.

5. Club of Rome / authors associated with the 2022 update (e.g., Earth for All). (2022). Earth for All: A Survival Guide for Humanity. New Society Publishers.

6. Catton, W. R. (1980). Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change. University of Illinois Press.

7. Rees, W. E. (2023). “The human ecology of overshoot: Why a major ‘population correction’ is inevitable.” ResearchGate.

8. Montgomery, D. R. (2007). Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations. University of California Press.

9. Tainter, J. A. (1988). The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press.

10. Jackson, T. (2009). Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. Earthscan.

11. Becker, E. (1973). The Denial of Death. Free Press.

12. Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). “The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory.” In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Public Self and Private Self. Springer.

13. Ripley, A. (2008). The Unthinkable: Who Survives When Disaster Strikes-and Why. Crown.

14. Jost, J. T., & Banaji, M. R. (1994). “The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness.” British Journal of Social Psychology.

15. Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much. Times Books.

16. Staw, B. M., Sandelands, L. E., & Dutton, J. E. (1981). “Threat-rigidity effects in organizational behavior: A multilevel analysis.” Administrative Science Quarterly.

17. Ellis, B. J., Figueredo, A. J., Brumbach, B. H., & Schlomer, G. L. (2009). “Fundamental dimensions of environmental risk: The impact of harsh versus unpredictable environments on the evolution and development of life history strategies.” Human Nature.

18. Dall, S. R. X., Giraldeau, L.-A., Olsson, O., McNamara, J. M., & Stephens, D. W. (2005). “Information and its use by animals in evolutionary ecology.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution.

19. Pellicano, E., & Burr, D. (2012). “When the world becomes ‘too real’: A Bayesian explanation of autistic perception.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences.

20. Nettle, D. (2010). “Why are there social gradients in preventative health behavior? A perspective from behavioral ecology.” PLoS ONE.

21. Bulley, A., & Pepper, G. V. (2017). “Cross-country relationships between life expectancy, intertemporal choice and age at first birth.” Evolution and Human Behavior.

22. Wikimedia Commons. (2025). Image/diagram: “Gas in a container/degrees of freedom”.

23. Holmgren, D. (2002). Permaculture: Principles & Pathways Beyond Sustainability. Permanent Publications

Brilliant article, thank you 😊

Thank you