If Collapse Is Inevitable, Why Does Seeing Early Matter?

The evolutionary role of Neurodivergence in a collapsing world

Editor’s note: My earlier essay, Collapse: A Framework sets out the structural dynamics of ecological overshoot and collapse. My previous essay, Why Some People See Collapse Earlier than Others looks at the link between neurodivergence and collapse awareness.

Here, I explore whether early perception of systemic breakdown (particularly among neurodivergent minds) serves an evolutionary function, not by preventing collapse, but by shaping how humans adapt when stability gives way to uncertainty.

Chapter 1: Seeing Clearly Is Not the Point

The collapse of global industrial civilisation is not a hypothesis that can be denied through optimism, faith in human intelligence, or technological innovation.¹

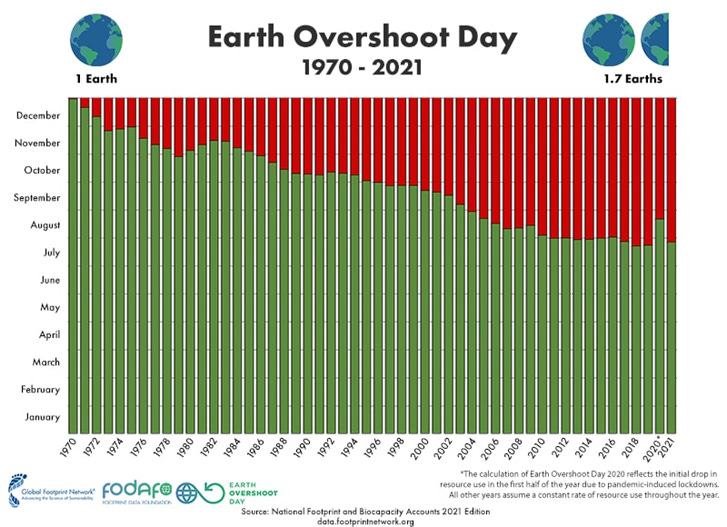

Collapse is a trajectory shaped by energy, ecology, and thermodynamics. Once a civilisation overshoots its biophysical limits, as ours did over 50 years ago, the outcome is not in question; only the timing, shape, and experience of the descent.²³

Fig 1: Earth Overshoot Day. (Source: Global Footprint Network) (2026)

Accepting that the collapse of industrial civilisation is inevitable, early awareness does not function the way people might assume it does. Awareness does not stop collapse. It does not meaningfully warn institutions that are structurally incapable of responding. Awareness rarely alters the behaviour of societies organised around growth, debt, and denial.⁴

So what, exactly, is the point of seeing early?

Much of the public discourse treats early collapse awareness as a form of prediction; a Cassandra role. The idea is that some people see the danger sooner, raise the alarm, and are tragically ignored. But this framing sneaks in a false assumption: that collapse is preventable if only the right people listen in time.

That assumption doesn’t survive contact with reality. Civilisations do not collapse because the people within them lacked information. They collapse because their internal logic demands continued expansion even as the conditions that supported that expansion disappear.

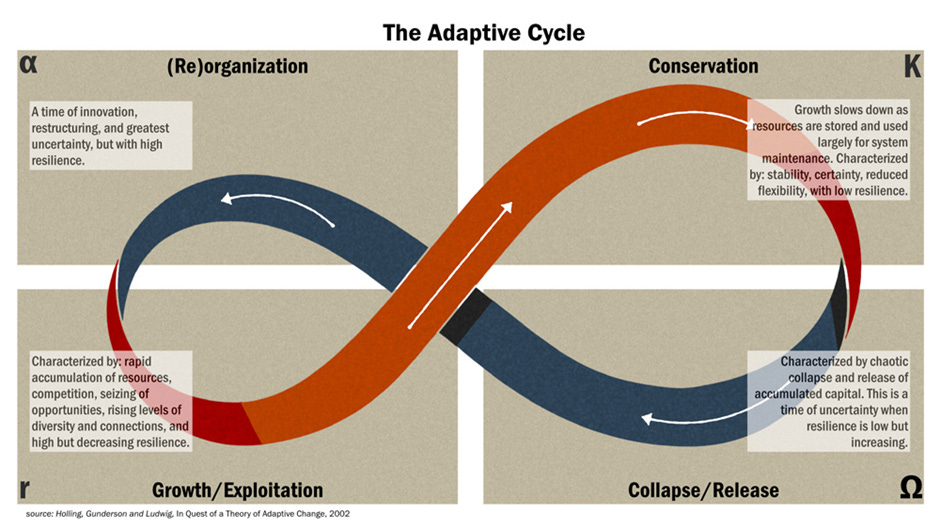

Every civilisation that has ever existed collapsed or disappeared, because that is what thermodynamically constrained systems do when they reach the release phase of the adaptive cycle.⁵⁶

Fig 2: The Adaptive Cycle. (Source: Island Press) (2002) (Source: Resilience.org) (2018)

Awareness does not override incentives to keep BAU going. Evidence does not dissolve power and inequality. Warning does not rewire systems built on denial.⁷

Early signals are often actively resisted because they threaten existing power arrangements and legitimacy structures. Environmental activists in the UK can be imprisoned now, just for discussing the possibility of protesting.

Institutions, like governments for example, are not neutral processors of information; they are stabilising mechanisms. Insights that imply contraction, limits, or loss are structurally inconvenient, and those who carry them are more likely to be marginalised than heeded.

So, if foresight alone cannot change the outcome, then early awareness must serve some other function, raising the question;

Why do some people see collapse coming anyway?

What purpose does that capacity serve if it cannot ‘save’ civilisation?

Collapse awareness emerges when certain minds register pattern convergence earlier than others. So, the question becomes; why, in every collapsing civilisation, a minority of people appear able to see the pattern forming long before it becomes undeniable; even when doing so offers no social reward, has considerable personal cost, and makes no difference to the civilisation’s downward trajectory anyway.⁸

If collapse is inevitable, then seeing early must be doing something other than trying to stop it.

This essay explores what that “something” might be.

Chapter 2: The Cost of Early Seeing

Empirical research on risk perception and systems collapse suggests that early recognition of systemic threat carries social and psychological costs. Individuals who identify large-scale environmental or civilisational risk ahead of consensus are more likely to experience social marginalisation, dismissal, and reputational damage, particularly when their assessments contradict dominant economic or political narratives (Kahan et al., 2012; Norgaard, 2011).⁹

As I discuss in Why Some People See Collapse Earlier than Others, emerging evidence suggests that early detection of systemic risk is patterned by differences in cognition, with neurodivergent individuals more likely to register converging signals, delayed feedback, and cross-domain inconsistencies before they are socially acknowledged.¹⁰

Early collapse awareness frequently produces a mismatch between perception and social validation. It also involves a form of grief that arrives early, before it is socially recognised or permitted, and is therefore carried in isolation, without shared language or ritual.

Without institutional endorsement, such perceptions are often framed by others as pessimism, irrational fear, or ideological extremism rather than as an assessment of risk. This dynamic can contribute to alienation and discourages further integration of insight into shared decision-making (Stoknes, 2015).¹¹

A common endpoint of this process is what is colloquially referred to as the ‘doomer’ position: a static conclusion of inevitability, often without corresponding adaptive response (aka, WASF).

Research on climate anxiety indicates that when threat perception is not paired with agency, meaning-making, or social support, individuals are more likely to experience paralysis, disengagement, or nihilism rather than sustained action (Clayton et al., 2017; Pihkala, 2020).¹²

This suggests that the primary difficulty is not early perception itself, but perception occurring in the absence of orientation frameworks capable of translating awareness into practice. Where cognition outpaces cultural response capacity, individuals are left carrying unintegrated risk knowledge alone, increasing the likelihood of withdrawal or fixation rather than adaptive mobilisation.¹³

For many people, the absence of adaptive response is a rational conclusion. If collapse is understood as biophysically inevitable, then attempts to ‘save’ civilisation appear misplaced. From this position, withdrawal or resignation makes sense.

However, this conflates two distinct questions: 1) whether industrial civilisation can be saved, and 2) whether humans can adapt to its contraction. Adaptive responses in this context are not oriented toward saving civilisation or avoidance of collapse. They are oriented toward resilience, continuity, and the preservation of function and life (all life) under declining conditions.¹⁴

Understanding why some individuals move beyond recognition of inevitability toward adaptive behaviour requires examination of the evolutionary purpose of cognitive variation itself.

Chapter 3: Neurodivergence as an Evolutionary Feature, Not a Bug

If neurodivergent traits were purely dysfunctional, they would not persist.

Importantly, this is not only a historical argument. Selection pressure is not frozen in the past, but acting in real time. Late-stage industrial civilisation is already exerting negative selection pressure on boundary-sensitive cognition within institutions, while simultaneously favouring those same traits outside them.

Burnout, exclusion, and withdrawal are not evidence of dysfunction, but signals of a changing adaptive landscape. That which doesn’t fit the dominant system may still be well-suited to the conditions emerging beyond it.

Autism, ADHD, and other atypical cognitive styles are highly heritable, stable across cultures, and present throughout human history. Large population and twin studies estimate heritability in the range of approximately 60–90%, with recent population-scale analyses placing it around 80%.²⁴

From an evolutionary perspective, that alone demands explanation. Natural selection is ruthless with traits that confer no advantage at all.

So, why are these minds still here?

One answer is that human survival has never depended on a single kind of intelligence. Our species did not evolve for harmony or social integration. The world has always been a dangerous place for humans, and so we evolved for uncertainty.

Anthropological and evolutionary research increasingly points to cognitive diversity as a group-level adaptation. Different minds attend to different signals. Most specialise in social cohesion and emotional attunement. Others in pattern detection, system building, long-range planning, or rule consistency. The value of this diversity is not evenly distributed across circumstances, but becomes visible under stress.¹⁶

Steve Silberman’s NeuroTribes reframed autism as a long-standing human variant that industrial society struggles to accommodate. Temple Grandin’s work similarly shows how autistic cognition often excels in domains requiring precision, visual reasoning, and systems thinking; traits that were historically vital in toolmaking, animal management, and environmental analysis.¹⁷

From an evolutionary standpoint, this makes sense. Groups that contained a mix of cognitive styles would have been more resilient than groups composed entirely of socially fluent generalists (neurotypical humans). When conditions were stable, conformity and cohesion mattered most. When conditions shifted (climate changes, resource depletion, migration pressure) the individuals who noticed anomalies, questioned assumptions, or fixated on underlying patterns found an important role.

Scott Page’s work on cognitive diversity demonstrates this mathematically; groups with varied ways of thinking consistently outperform homogeneous groups on complex, uncertain problems. Not because every individual is ‘better’, but because difference itself is adaptive.¹⁸

This reframes neurodivergence entirely. It is not a mistake in the code, but a variation maintained because in unstable times it matters more than social cohesion.

David Epstein’s Range builds on this. In environments where rules are clear and feedback is immediate, specialists thrive. In environments where conditions change rapidly and rules break down, pattern-based and multidisciplinary thinkers gain an advantage. Collapse (ecological, energetic, and institutional) is precisely such an environment.¹⁹

Seen this way, neurodivergent minds are maladaptive for late-stage bureaucratic civilisation. They are optimised for detecting when systems stop making sense and complexity begins to break down.

This also explains why modern institutions struggle so badly with neurodivergence. Schools, workplaces, and professional cultures reward compliance, time-based organisation, and social performance. They are designed for efficiency in stable systems. Traits that once provided early warning cause friction in the dominant culture.

But evolution does not optimise for stability. It optimises for species survival across cycles.²⁰

Chapter 4: Collapse as a Context Shift

Industrial civilisation can be understood as an extended stability bubble.

For several centuries, high energy surplus, expanding material throughput, and institutional continuity have allowed social, economic, and political systems to absorb stress without fundamental reconfiguration. Within this context, certain cognitive and behavioural traits are reliably rewarded: social attunement, norm adherence, consensus maintenance, and short-to-medium-term optimisation.

During prolonged periods of stability, neurotypical traits optimise for cohesion. Sensitivity to social cues, trust in institutional continuity, and preference for incremental change all support coordination at scale. These traits are central to the functioning of complex societies under stable conditions. They reduce internal friction, and maintain shared narratives that allow systems to persist and expand.

Neurodivergent traits, by contrast, often sit uncomfortably within such environments. Reduced sensitivity to social consensus, heightened attention to internal consistency, and low tolerance for unresolved contradiction are less rewarded when systems are functioning within expected parameters. In stable contexts, these traits can appear maladaptive, disruptive, or socially dysfunctional.

Civilisational collapse flips this relationship.

As ecological, energetic, and material limits assert themselves, the problem space transitions from growth to constraint navigation. The relevant queries become how to detect boundary conditions, recognise failure modes, and adapt behaviour under irreversible decline.

In such contexts, traits associated with neurodivergence (system-level pattern recognition, reduced reliance on social validation, and willingness to follow implications to uncomfortable conclusions) become functionally relevant.

This does not imply a reversal of value, nor a simple inversion where one cognitive style replaces another. Cohesion broadly remains necessary. But the adaptive balance changes, and systems entering contraction require both maintenance and edge sensing. Historically, human groups that navigated environmental stress successfully did so by integrating diverse cognitive roles, including those oriented toward early detection of risk.

Collapse is a context shift that alters which forms of cognition are legible, tolerated, and useful. Understanding this shift clarifies why certain individuals experience early recognition as alienating, and why the same traits may become increasingly salient as conditions deteriorate.

Put another way, trait adaptiveness is context dependant.

The implications of this shift concern how perception is translated into response. So, what is early sensing actually for once collapse is accepted?

Chapter 5: From Prediction to Preparation

Early recognition of systemic risk is often misinterpreted as predictive capacity: the ability to foresee collapse before others do. This framing is misleading. Prediction, in complex systems, has limited value once boundary conditions/tipping points are crossed. The relevant shift is moving from abstraction to preparation.

Historical and anthropological evidence suggests that individuals who recognised ecological or social instability early rarely functioned as prophets in the modern sense, but had practical roles. They became builders of parallel structures, custodians of skills that were losing institutional support, and organisers of local systems capable of functioning under degraded conditions. Their activity was oriented toward continuity.

This pattern appears repeatedly in periods of contraction. As centralised systems lose reliability, adaptive responses migrate downward: toward household production, local provisioning, informal networks, and skill transmission outside formal institutions. Early recognition of instability allows earlier engagement in this process. It creates time to experiment, fail, adjust, and embed practices before necessity removes choice.

A familiar example is the withdrawal of Roman authority from Britain in the late fourth and early fifth centuries. The collapse was not sudden; coin circulation declined, road maintenance ceased, military pay became erratic, and central provisioning failed decades before imperial administration formally ended. Those who waited for restoration (for Rome to return, for legitimacy to be reasserted) were left exposed.²¹

Those who adapted earlier shifted toward local production, reused materials, re-embedded skills, and reorganised around kinship and land rather than imperial logistics. Archaeology shows continuity of life at smaller scales long after imperial systems vanished. What mattered was not predicting the end of Rome, but disengaging from its provisioning logic early enough to build alternatives. ²²

Contemporary responses such as permaculture, mutual aid networks, repair cultures, and community skill-sharing should be understood in this context. They are post-predictive responses: practical adaptations once the trajectory is recognised and accepted. Their value lies in resilience under constraint.

Seen this way, early awareness is not about seeing the future more clearly. It is about exiting the predictive frame altogether and reallocating attention toward what remains viable as systems lose coherence.

Chapter 6: Why Some People Can’t Stay in the System

A recurring observation within collapse-aware communities is that many individuals who recognise systemic decline early struggle to remain functional within conventional employment structures. This is often framed as personal failure, poor resilience, or psychological fragility. The evidence suggests otherwise.

Late-stage institutional systems increasingly prioritise performative compliance over functional contribution – appearing busy but achieving nothing. Early perception is structurally incompatible with growth logic; it resists the suppression of contradiction required to maintain high-throughput systems once their internal coherence begins to fail.

Work becomes oriented toward maintaining appearances, narratives, and procedural continuity (meetings, metrics, slide sets and reports) rather than delivering outcomes aligned with material reality. For individuals whose cognition prioritises internal consistency, system integrity, and factual alignment, this creates escalating pressure. .

Neurodivergent traits amplify this mismatch. Where neurotypical cognition often optimises for social cohesion and role performance, neurodivergent cognition is less tolerant of sustained contradiction between stated purpose and observed function. As institutional legitimacy erodes internally, the effort required to mask this dissonance increases sharply.

Masking is the learned neurodivergent practice of suppressing or modifying one’s natural ways of thinking, communicating, and behaving in order to meet social, professional, or institutional expectations, often at significant cognitive and emotional cost.²³

Masking can more easily be sustained when the system being upheld is perceived as broadly legitimate. As perceived legitimacy erodes, masking increasingly becomes a form of self-estrangement. Work turns into performance without meaning, and continued participation carries psychological cost without compensating value.

This strain is better understood as moral injury rather than psychological fragility. Sustained participation in systems that violate one’s sense of truth, coherence, or purpose produces harm, particularly for minds less buffered by social rationalisation. When work requires maintaining narratives that contradict observed reality, distress arises from fidelity to reality.

Much of the contemporary support framework for autistic people is oriented toward accommodation within existing systems: improving employability, reducing social friction, and increasing tolerance for late-stage institutional norms. That orientation assumes the legitimacy and durability of those systems.

The role I describe here is fundamentally different; it does not aim to optimise autistic individuals for participation in a civilisation already in structural decline. It recognises that some cognitive profiles are poorly suited to sustaining high-throughput, legitimacy-eroding systems precisely because they are better attuned to boundary conditions, contradiction, and failure.

I am not claiming that neurodivergent people are better adapted to collapse, but that cognitive variance preserves response diversity when throughput-driven logic fails.

Support, in this context, is not about better fitting neurodivergent minds into a deteriorating order, but about allowing those minds to disengage earlier and redirect effort toward forms of continuity that remain viable as complexity contracts.

In other words, the problem is not that some minds fail to fit the system; it is that the system is entering a phase where fitting it no longer makes sense at all.

Chapter 7: The Point of Seeing Early

Early awareness is frequently misunderstood as an attempt to warn others. This assumption leads to predictable frustration: resistance, dismissal, and social friction.

Seeing early alters how we can allocate our energy. It changes time horizons and investment decisions, and impacts social commitments. It reshapes relationships to land and work, and alters how obligation is understood. Most importantly, it allows disengagement from systems that extract energy while offering diminishing future value.

These reallocations do not scale upward in the conventional sense, but they do scale sideways. Many small acts of disengagement and reorientation alter future possibility without coordination or visibility. Continuity is produced by countless decisions about where energy is no longer spent.

Early perception does not function to optimise outcomes or confer advantage, but to preserve variance in how humans respond as systems destabilise, keeping multiple pathways open when throughput maximisation itself becomes a liability.

Resources are finite. Attention, labour, and care spent sustaining declining structures are unavailable for building what may persist longer under constraint.

Early recognition allows this shift to occur gradually rather than reactively. It provides time to step down dependency, simplify arrangements, and develop alternative competencies before disruption imposes them abruptly.

It’s plausible that cognitive diversity increases population resilience across collapse cycles, and neurodivergent traits persist because they expand the range of viable responses under changing conditions.

The value of early seeing lies here: in early adaptive responses.

Chapter 8: A Different Measure of Usefulness

Industrial society measures usefulness through productivity, influence, and growth. These metrics assume stable inputs, expanding throughput, and long planning horizons. Under conditions of contraction, they lose relevance and a different set of measures come into play.

Soil built rather than extracted. Skills shared rather than credentialed. Children supported rather than tested. Small systems that persist under stress. These outcomes do not scale cleanly and are often invisible to institutional accounting. They matter anyway.

Neurodivergent traits find clearer alignment within these domains. Attention to detail, systems thinking, long-term pattern recognition, and resistance to social signalling over substance become assets rather than liabilities.

It is possible that neurodivergent traits persist because they widen the species’ adaptive range across collapse cycles. In that sense, variation is preserved not to prevent collapse, but to survive it unevenly.

Usefulness, in this frame, is ecological (rather than economic). It concerns contribution to continuity under pressure, not growth within expansionary logic.

Within this framework, attempts to ‘cure’ autism sit uneasily with both evolutionary logic and collapse-aware realism. If neurodivergent cognition persists because it confers adaptive value under conditions of uncertainty, instability, and systemic transition, then treating autism as a pathology to be eliminated reflects a civilisation-specific bias rather than a species-level insight.

Cure-oriented framings assume a stable social environment to which all minds should be optimally fitted; they presuppose that the primary problem lies in the individual rather than in the mismatch between cognitive variation and the demands of a late-stage, high-throughput system.

From an evolutionary perspective, eliminating boundary-sensitive, pattern-detecting, and consensus-resistant cognition would amount to narrowing the species’ adaptive range precisely at a moment when diversity of perception and response is most needed.

In this sense, cure narratives are not just medical projects but expressions of a cultural commitment to preserving a particular mode of social organisation - one already losing its ecological and energetic foundations, even as its language of permanence persists.

Within this framework, neurodivergence is not something to be corrected for the sake of ‘fitting in’, or civilisation’s continuity, but a form of variation whose value becomes most visible as that civilisation enters decline and collapse.

Chapter 9: Autistic Fixation, Overshoot, and the Turn Toward Generalism

Autistic cognition is, in part, described in terms of fixation or obsession. This framing is misleading, and what is being labelled is not compulsive interest but sustained attention directed toward resolving inconsistency. Autistic minds tend to remain with a problem until its internal logic closes. Where explanations remain partial or contradictory, attention will not easily disengage.

Overshoot functions as a powerful attractor in this context. It provides a unifying explanation that resolves multiple domains simultaneously: energy, ecology, economics, culture, health, and governance. Once overshoot is recognised, many previously disparate failures align into a single systemic pattern.

As complexity contracts, feedback shortens and truth becomes locally actionable again: claims meet reality directly, consequences are harder to defer, and coherence is tested through action rather than stories.

Early engagement with collapse often begins as autistic specialism. Individuals go deep into energy descent, climate dynamics, thermodynamics, or systems theory. This is how understanding stabilises. But collapse cannot be fully grasped within any single discipline. Overshoot is inherently cross-discipline, and as the model grows, depth alone becomes insufficient.

This shift can appear counterintuitive; from specialism toward generalism. Not the narrative-driven generalism of managerial culture, but integrative generalism built from deep models. Domains are not sampled casually, but are pulled together because the problem demands it. Collapse forces synthesis.

Life-positive responses like permaculture emerge naturally from this process. It is adopted as a system that closes loops under constraint. Inputs and outputs are visible. Feedback is immediate. Claims are testable. Failure is legible. For collapse-aware autistic cognition, this is an embodied response that matches how the mind already works.

In the context of overshoot and collapse, what appears externally as obsession is better understood as orientation. What appears as a shift away from autistic traits is, in fact, their extension into a context where coherence requires holding many disciplines at once.

Chapter 10: Closing Thoughts

This essay continues exploring the ideas begun in my earlier essay ‘Why Some People See Collapse Earlier than Others.’

The first essay recognised that some people perceive systemic limits earlier than others. The second situated it within evolutionary variation rather than individual pathology. What follows is orientation toward responses that make sense when the false promises of our civilisation fall away.

Early seeing leads to realignment, realignment leads to ecological engagement, and ecological engagement leads to new roles.

Roles that become intelligible only when the wider story is understood: industrial civilisation as a transient stability phase; collapse as a context shift; neurodivergent cognition as part of the species’ adaptive range.

Nothing about this confers status. It does not make collapse avoidable. It simply explains why certain responses emerge, and why they persist once the trajectory is accepted.

Neurodivergent people do not carry a responsibility to warn, lead, or compensate for a civilisation in decline. Boundary-sensing traits are not a moral assignment; they are a by-product of variation that becomes visible under certain conditions.

Some individuals perceive systemic failure earlier because their cognition is less stabilised by social consensus and institutional legitimacy.

What follows from that perception is a choice; many withdraw. Some adapt quietly and locally. Others do nothing at all. There is no obligation attached to seeing clearly. There is only the option to redirect one’s own energy once the old narratives stop holding.

Demands that early perceivers take responsibility for warning or fixing things often function to manage others’ anxiety about loss of control, not to express a genuine moral duty.

Seeing early does not make you responsible for the future; it makes it possible to leave the past sooner.

My writing will always remain free to access. If it resonated with you, please consider liking and sharing - that’s how this work travels. You’re very welcome to subscribe if you want to follow where these ideas go next.

References

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens, W. W. (1972). The Limits to Growth. Universe Books.

Catton, W. R. (1980). Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change. University of Illinois Press.

Rockström, J. et al. (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461, 472–475.

Stoknes, P. E. (2015). What We Think About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming. Chelsea Green.

Tainter, J. A. (1988). The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press.

Holling, C. S. (2001). Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems.

Norgaard, K. M. (2011). Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life. MIT Press.

Smil, V. (2017). Energy and Civilization: A History. MIT Press.

Kahan, D. M. et al. (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy. Nature Climate Change.

Baron-Cohen, S. (2012). The Science of Evil: On Empathy and the Origins of Cruelty. Basic Books.

Stoknes, P. E. (2015). (see above).

Clayton, S. et al. (2017). Mental health and our Changing Climate. American Psychological Association.

Pihkala, P. (2020). Anxiety and the ecological crisis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders.

Folke, C. et al. (2010). Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability).

Crespi, B. (2016). Autism as a disorder of high intelligence. Frontiers in Neuroscience.

Henrich, J. (2016). The Secret of Our Success. Princeton University Press.

Silberman, S. (2015). NeuroTribes. Avery.

Page, S. E. (2007). The Difference. Princeton University Press.

Epstein, D. (2019). Range. Riverhead Books.

Wilson, D. S. (2012). The Social Conquest of Earth. Liveright.

Bowden, W (2021). The fall of Roman Britain: how life changed for Britons after the empire. History Extra.

Radley, D (2025). New study shows Britain’s economy did not collapse after the Romans left. Archaeology News.

Pearson, A et al. (2021). A Conceptual Analysis of Autistic Masking: Understanding the Narrative of Stigma and the Illusion of Choice. PMC

Sandin et al. (2017). The heritability of autism spectrum disorder. JAMA

I feel so seen🥰

Adrian, please some personal info about you, your personal story, trajectory and how to came to articulate Collapse so eloquently. This essay’s brilliance consolidates my understanding to where we are collectively. I will continue to forward these to my Collapse Resilience group here in Taos, NM as we build our local response to our early awareness, although there are different ways to define “early.” The Beat and Hippie generations of which I am one, were early precusors of Collapse Awareness.